“As a slave, the social phenomenon that engages my whole consciousness is, of course, revolution. Revolution should be love inspired,” earnest words spoken by the activist, author and co-founder of the Black Guerilla Family, George Jackson. Noted as one of the architects of the Prisoners’ Rights Movement, the origins of Black August is based on his life story. At the age of 18, George Jackson was jailed for allegedly stealing $70 dollars from a Los Angeles gas station. Although there was evidence of his innocence, he was given an indeterminate sentence of one year to life. From the confines of prison, George became one of the most powerful revolutionary voices and one of greatest living threats to the U.S. power structure. Like Malcolm X before him, George educated himself profusely behind prison bars to the point he became a hyper-intellectual, a leading theoretician for the prison movement and a black freedom fighter. Inspired by the teachings of Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong, Karl Marx and other socialist and communist ideologies, George’s political ideals became popular and widespread. His landmark book, Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters Of George Jackson sold over 400,000 copies, nationally and internationally. His second book, Blood In My Eye also became a bestseller. In 1966, George co-founded the Black Guerilla Family with W.L. Nolen. He was also a prominent member of the Black Panther Party. George ’s presence is imprinted on abolitionism.

George Lester Jackson was born on September 23, 1941, in Chicago, Illinois. He was raised by loving parents, Lester Jackson and Georgia Bea Jackson and was the second born among the couples’ five children. Given special attention by his grandfather, George “Papa” Davis, whom he credits for instilling in him life principles and values, he would often share meaningful simple thought-provoking allegories. By 1956, the family had relocated to Los Angeles, California.

In 1960, George was arrested for allegedly stealing $70 from a gas station in Los Angeles. Although there was evidence of his innocence, his court-appointed lawyer maintained that because he had a record (two previous instances of petty crime), he should plead guilty in exchange for a light sentence in the county jail. George described the incident in a letter, “…when I was accused of robbing a gas station of seventy dollars, I accepted a deal. I agreed to confess and spare the county court costs in return for a light county jail sentence. I confessed but when time came for sentencing, they tossed me into the penitentiary with one to life.”

He spent the next 10 years in Soledad Prison, seven and a half of them in solitary confinement. Instead of succumbing to the dehumanization of prison existence, he transformed himself into the leading theoretician of the prison movement and a brilliant writer.

He began to be involved with what was considered “revolutionary” activities for fighting back against the white supremacy power structure, when he met and befriended a man named W.L. Nolen. W.L. Nolen introduced him to the teachings of well known socialist and communist leaders. “I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, and Mao when I entered prison and they redeemed me,” George wrote in a letter.

In 1966, both he and W.L. Nolen started the Black Guerilla Family (BGF) as a political entity based on anti-racist class analysis and struggle. In 1969, W.L. Nolen initiated a class action law suit on human rights violations (1969 W. L. Nolen, et. al. v. Cletus Fitzharris), in which he charged the prison superintendent and prison guards with knowingly exacerbating “existing social and racial conflicts” through “direct harassment and in ways not actionable in court.” These actions included repressive prison tactics of filing false disciplinary reports and leaving Black inmates’ cells unlocked for racist assaults and “placing fecal matter or broken glass in the food served to “New Afrikans.” W.L. Nolen feared for his life as a plaintiff.

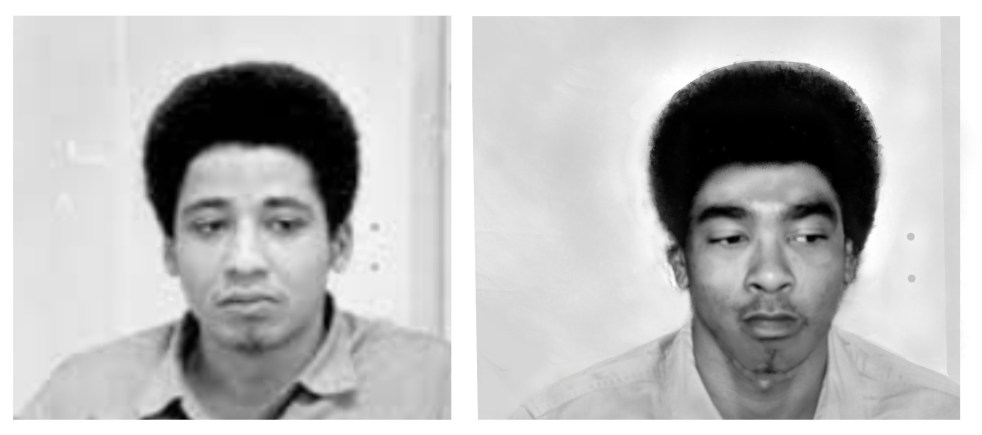

Four months after W.L. Nolen filed his petition, he and two other Black prisoners (one of which who had signed it) were killed by a corrections officer at Soledad Prison. Three days after the killings were ruled justifiable homicide, a white guard named John V. Mills was killed. Without evidence, the prison authorities charged George and two other inmates (Fleeta Drumgo, and John Clutchette) with the death of Mills. The three became known the “Soledad Brothers.” A conviction spelled an execution in the gas chamber at San Quentin. It was suspected that the state of California was trying desperately to kill its incarcerated revolutionaries.

Led by George, the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee included Faye Stender, Georgia Jackson (his mother), and Angela Davis. Faye Stender defended him in court. George and Angela Davis began to date while George was still imprisoned and considered each other husband and wife.

On August 7 1970, George’s brother, Jonathan (a 17-year-old high school student from Pasadena) invaded the Marin County courthouse during a court hearing. With guns that had been registered under Angela Davis’s name, he handed weapons to three black San Quentin inmates and took five hostages (a judge, the D.A. and 3 jurors). Jonathan held the hostages in exchange for the freedom of the Soledad Brothers, and the life of his brother George. As he left with the inmates and five hostages a shootout ensued, killing Jonathan, two of the inmates (William Christmas and James McClain) who had assisted him, and Judge Harold Haley.

Hundreds of miles away, Angela Davis was charged in relation to the shootout because the guns used by Jonathan were registered in her name. She was added to the FBI’s Most Wanted List. Upon her capture, Richard Nixon congratulated the FBI for apprehending “the most dangerous terrorist” in the country. Angela Davis would later be acquitted of all charges, in a trial that would go down in the annals of the Black Power Movement .

In the fall of 1970, George released his first book Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. He dedicated it to Jonathan, Angela and his mother. Soledad Brother was released to critical acclaim in France and the United States, with an introduction by the renowned French dramatist Jean Genet. The book contained letters that he had written from 1964 to 1970, in his testament. Soledad Brother went on to become a classic of Black literature and political philosophy, selling more than 400,000 copies before it went out of print thirty years ago.

Later that year, George wrote Blood in My Eye, a text heavily laced in insurgence which was influenced by his brother Jonathan. This book also became a bestseller. Edited by Toni Morrison, it was eventually published posthumously by Random House.

On August 21, 1971, just two days before the opening of his trial, an uprising transpired at the San Quentin Prison. The prisoners overpowered the guards. In a purported escape attempt, George was shot to death by a tower guard.

The day after George died, his distraught father Lester Jackson shared on Oakland television that his eldest son confided to him that prison guards had starved and denied George clean drinking water for three days. Mr. Jackson’s grief-stricken interview also informed the public that George told Jonathan Jackson in late July 1970 that guards had promised to kill George on August 10th. “No Black person,” wrote James Baldwin, “will ever believe that George Jackson died the way they tell us he did.”

George’s funeral was held on August 28, 1971 at St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland, California. There were 8,000 people in attendance. Days prior to his death, George had rewrote his will, leaving all royalties, as well as control of his legal defense fund to the Black Panther Party.

Several notable artists, entertainers and writers have dedicated their work to George’s memory or have created works based on his life. Bob Dylan released a single George Jackson, about the life and death of George. Soulja’s Story, a single released by Tupac and Get Down a single by Nas, both make references to the Marin County incident. Other artist-creatives include Ja Rule, Archie Schepp, Joan Boaz, Stephen Jay Gould, Stanley Williams, reggae band Steel Pulse and hip-hop trio Digable Planets.

SPECIAL NOTE:

There is a misclassification of the Black Guerilla Family being referred to as a gang, instead of their correct identification as an educational organization. This tactic has been used by the California Department of Corrections (CDCR) for decades as a means to target its members (all black) for punitive action to repress their efforts to organize and to educate. In 2015, as part of a court settlement, the CDCR was ordered to no longer identify members of the Black Guerilla Family as being “gang affiliated.”

QUOTES:

“As a slave, the social phenomenon that engages my whole consciousness is, of course, revolution. Revolution should be love inspired.”

“I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, and Mao when I entered prison and they redeemed me.”

“Capture, imprisonment, is the closest to being dead that one is likely to experience in this life,”

“Why do we accept this sort of thing? We have numerical superiority — but they have guns and money. And then the righteous don’t like to cut throats, so we languish in misery.”

“There are still some Blacks here who consider themselves criminals, but not many.”

SOURCES:

http://www.aaihs.org/george-jackson-dragon-philosopher-and-revolutionary-abolitionist

https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/rodneyjackson.html

therealnews.com/george-jacksons-unfinished-revolution

blackwithnochaser.com/the-origins-of-black-august

https://socialistworker.org/2018/08/21/the-murder-of-a-soledad-brother

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Jackson_(activist)

https://www.freedomarchives.org/George%20Jackson.html

https://www.vibe.com/features/editorial/nas-tupac-george-jonathan-jackson-602888/

files.libcom.org/files/soledad-brother-the-prison-letters-of-george-jackson.pdf

sfbayview.com/2020/09/the-black-guerilla-family-is-not-a-prison-gang-but-an-educational-organization/

medinaorthwein.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/3-1ErrataAmendedComplaintforDamagesandDeclaratoryandInjunctiveRelief.pdf

ccrjustice.org/sites/default/files/attach/2015/06/Supplemental%20Complaint.pdf

CREDITS:

Recreate Model: A.J. Gore

Photographer & Editor of the Recreated Photo: Jasmine Mallory